Feeding the world sustainably starts with how you run

your agribusiness

Make better decisions based on your data with cutting-edge genetics,

strategic economic analysis, and the latest agribusiness developments

“A big leap forward in terms of how we are modernizing our breeding operations”

— Hugo Campos, Director of Research, International Potato Center (CIP), Uganda

Feeding the world sustainably starts with how you run

your agribusiness

Make better decisions

based on your data with

cutting-edge genetics,

strategic economic analysis, and

the latest agribusiness

developments

“A big leap forward in terms of how we are modernizing our breeding operations”

— Hugo Campos, Director of Research, International Potato Center (CIP), Uganda

You want to respond to climate change.

You want to respond to consumer choice.

And you want better business outcomes.

These goals aren’t mutually exclusive. In your experience, they depend on one another.

Premium crops and healthy, reliable livestock need fewer resources to produce greater yields.

A smaller environmental footprint helps you stay ahead of the policies pressuring your industry.

Which means you’ll see higher feed efficiency and significant savings on inputs like irrigation, fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, and pharmaceuticals. And worry less about environmental fines and compliance.

All of this is within reach when you use mathematical genetics, digital technologies, and economic insights to unlock value that just didn’t exist before.

Dr Tim Byrne and Dr Bruno Santos working on the NextGen Cassava Breeding Project with Cornell University and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA)

You already collect plenty of data.

Now you can finally turn it into actionable insights.

“What IS the impact of our business decisions?”

Better strategy means better results. With AbacusBio, you get access to strategic insights across every step of the value chain.

From seeds, breeds, and processing all the way into people’s homes.

Improve the sustainability of your sector with environmental genetics

Develop successful new processes and products based on data science

Increase feed efficiency

Strengthen food and fiber security in the face of droughts, flooding, and soil degradation

“Which genetic traits will REALLY make a difference?”

The days of breeding for beauty and traditional standards are over. Because the performance of crops and livestock means so much more now. You want to help feed the world, reduce emissions, and offer the produce people are asking for.

Achieve higher, reliable yields with more efficient resource use

Decrease the methane or nitrogen emissions of your agribusiness – or even the entire industry

Improve animal health and welfare

Depend less on pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizer

Run a more profitable business by aligning with consumer and market requirements

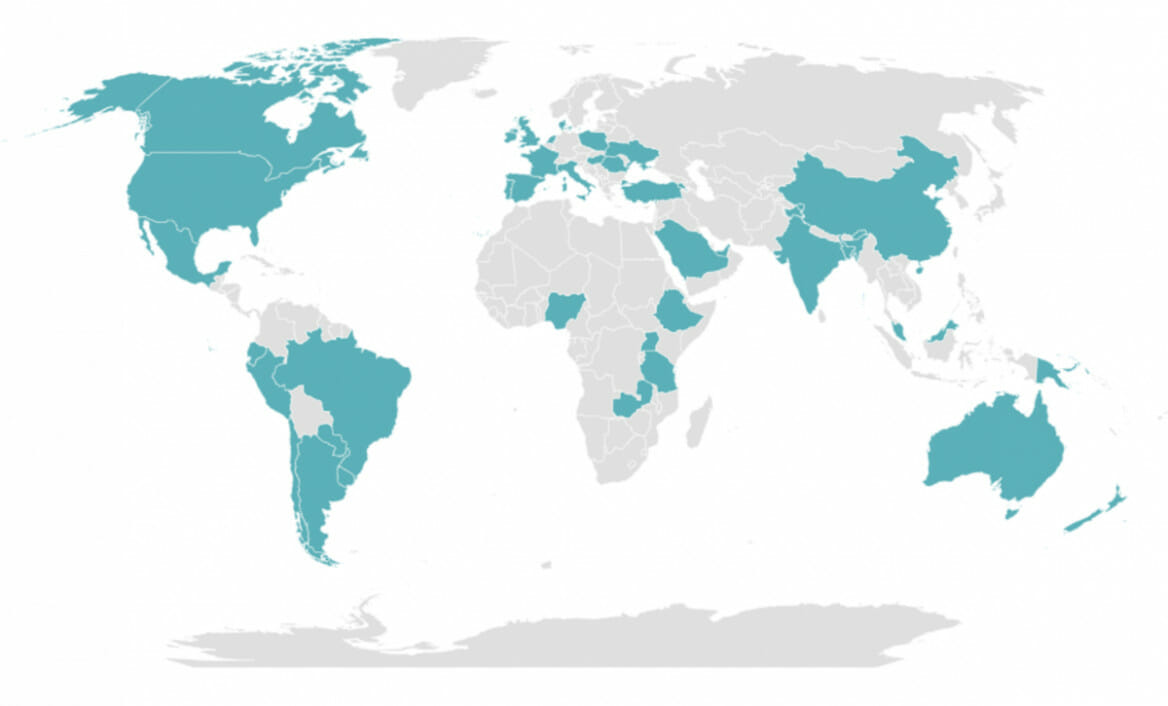

Wherever you are, we meet you right there

Our expertise has been peer-reviewed, tried, and tested with businesses around the world

Armenia

Australia

Bangladesh

Brazil

Brunei

Canada

Chile

China

Denmark

Ecuador

Ethiopia

France

Hungary

India

Ireland

Italy

Malaysia

Mexico

Netherlands

New Zealand

Nigeria

Papua New Guinea

Paraguay

Peru

Poland

Romania

Saudi Arabia

Tanzania

Turkey

Uganda

UK

Ukraine

United Arab Emirates

United States

Uruguay

Zambia

Testimonials

You’ll be pleased to know there’s no homework to get started

You may have done lots of research we can draw on already. Maybe you’re just starting to explore the possibilities. Either way, now is the time to take advantage of our expertise.

Right from the start, you’ll learn exactly which steps you can take to systematically collect better, more uniform data.

So you can let the facts show you how to outperform your competition, protect the environment, and respond to what customers want.

Dr Cheryl Quinton and Megan McCall

evaluating the impact of new technologies for investment decision making

“AbacusBio knows what we need”

“AbacusBio are really good at grasping what it is we need out of a project. And they take the initiative on day-to-day work, which is really helpful.”

Kim Matthews

Head of Animal Breeding & Product Quality, ADHB

“Great project management”

“I really like the way that AbacusBio manage projects and break things down into usable chunks.”

Brian Gardunia

Head of Cotton Product Design, Bayer